|

| The Pacific Remote Islands are Micronesian Islands |

Scoping Comments for the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Proposed Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Sanctuary

Prepared by Angelo Villagomez

Submitted May 23, 2023

My name is Angelo Villagomez and I am currently a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress and an Indigenous Chamorro ocean advocate from the Northern Mariana Islands. For the last 15 years I have advocated for the designation and active management of marine protected areas in the United States and across the globe, including the Mariana Trench, Pacific Remote Islands, and Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monuments. I founded the Friends of the Mariana Trench and wrote the nomination for the proposed Mariana Trench National Marine Sanctuary; I am also the conservation chair for the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument community group and co-lead the Ocean Workgroup for the America the Beautiful for All Coalition.

I offer the following comments on the scope and significance of issues to be addressed in the draft environmental impact statement for the proposed Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Sanctuary:

There are multiple roads the United States can take to achieve 30% protection of the ocean by 2030. Recent scientific evidence suggests that the who and how of conservation can be just as important, if not more so, as the what and where. Achieving 30x30 on the ocean and in the spirit of the America the Beautiful Initiative will require Free, Prior, and Informed Consent in designating a large network of geographically representative marine protected areas that are equitable, just, well-designed, well-managed, funded, and staffed.

I support the advancement of national marine sanctuaries as a critical tool towards achieving the goals of the America the Beautiful Initiative, President Biden’s national call to action to address climate change, improve access to nature for all Americans, and conserve and restore 30 percent of U.S. lands and waters by 2030. I am particularly supportive of efforts that engage with and follow the leadership of Indigenous peoples in conservation. The US Pacific territories, which comprise 29% of the United States’ exclusive economic zone and are home to Chamorros, Samoans, and several Micronesian groups, will be critical for delivering ocean climate solutions. In fact, the US Pacific territories and Hawaii are already home to 96% of the marine protected areas in the country, and 99.5% of the marine reserves.

The significant history and natural resources of the Pacific Remote Islands are essential to the fabric of the American story, and play a role in interpreting our past, present, and future, as both a celebration of Indigenous peoples and a sober reflection upon Manifest Destiny and the American empire. The great Pacific scholar Epeli Hauʻofa wrote: “There is a world of difference between viewing the Pacific as 'islands in a far sea' and as 'a sea of islands.' The Pacific Remote Islands presents us with a sea of islands, as a connected, vibrant, and abundant realm which we must steward with our Indigenous values, including both Inafa’maolek (doing/making good) and Respetu (respect).

The seven islands that make up the Pacific Remote Islands are stepping stones that connect Hawaii and Micronesia both culturally, biologically, and historically. For millennia, as traditional voyagers traversed across the waves, following seabirds to far flung destinations, fish and larvae in the water migrated across Necker Ridge, an undersea mountain range connecting Johnston to the Hawaiian Islands. In more modern times, after the designation of the exclusive economic zone in 1983, industrial fishing fleets from Hawaii and American Samoa plied the surrounding waters for tuna and other fish.

Colonialism has historically pitted Indigenous peoples against one another, and to avoid this today, when we explore our shared Pasifiku histories, cultures, and identities, we must do so in a respectful and intentional manner to ensure advocacy for one perspective allows space for the other. The value of the proposed sanctuary can and should be interpreted through its connection to Hawaii, but it must also center its connection to Micronesia.

The Hui Panalāʻau (translated as “society/club of colonizers”) – the 130 young men who colonized three of the islands in the years before World War II – were mostly Hawaiian. But the Indigenous peoples who have the strongest cultural and historical connections to the Pacific Remote Islands identify as Micronesian. Wake Island is geographically, culturally, and historically linked to the people of the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Kingman, Palmyra, Jarvis, Howard, and Baker are similarly connected to the Republic of Kiribati. Make no mistake, the islands in the proposed Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Sanctuary are Micronesian islands.

Most of my policy comments draw from the following three articles, and echo previous recommendations I have made to the Biden administration:

Proposed National Marine Sanctuaries Provide a Pathway Toward Indigenous-Led Ocean Conservation

US Pacific Territories and the America the Beautiful Initiative Can Deliver Ocean Climate Solutions

5 Ways Scientists, NGOs, and Governments Can Support Indigenous-led Conservation

Information on the biological and cultural resources of the Pacific Remote Islands are drawn from these three articles I have published elsewhere (these are cited repeatedly in the sanctuary proposal):

Management goals or actions

Regulatory framework most appropriate for management of the proposed sanctuary

During the NEPA process, at the earliest opportunity, the territorial governments of Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa should be approached and be invited to become cooperating agencies by agreement with NOAA in accordance with 40 CFR 1501.8. Federal funding should be identified to support this participation, as this will undoubtedly be a heavy burden for territorial governments and communities.

The public scoping process should include coordination with the executive and legislative branches of the territorial governments of Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa, and their respective delegates to the United States Congress.

NOAA should request specific co-management agreements between local Indigenous communities and governments and the United States. This is a critical step to right historical wrongs and enable Indigenous government leadership on sanctuary governance and administration. In the Pacific Remote Islands, this will include governments and communities in Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa, and Hawaii.

Move management decision-making power out of Hawaii and back to the territories, both in terms of where full time employees are located, and with co-management/co-stewardship agreements. In particular, efforts should be made to engage the Indigenous American Samoan, Chamorro, and other Micronesian peoples and territorial governments who are long-time stewards and owners of these resources, and consider headquartering the proposed sanctuary in one of the US Pacific territories. This would increase access for several Indigenous peoples to engage in natural resources management and is in line with the Biden administration’s Justice40 Initiative.

NOAA should establish a pre-designation Pacific Remote Island Sanctuary Advisory Council that would eventually form the official sanctuary advisory council after designation. The advisory body would help NOAA to prepare the draft environmental impact statement, and the advisory council’s continuity from pre-designation to post-designation would ensure that its members understand the sanctuary’s conservation needs. The advisory body could be similar to the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument Community Group, but seats should be added to represent Micronesian and Samoan Culture, and each of the three governments from Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa, and possibly other perspectives. The history, culture, and perspectives of Micronesia and Micronesians are sorely lacking from the management of the existing monument and in the documents of the proposed sanctuary.

Other information relevant to the designation and management of a national marine sanctuary.

NOAA and the Department of Interior should convene a nomenclature committee to review the names of all sites within the proposed national marine sanctuary, establish protocols for future naming, and ensure that all names reflect the history and cultures of the people who are the longtime stewards and owners of sanctuary resources, which includes the US territories (Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa), neighboring countries (Republic of Marshall Islands, Republic of Kiribati, and possibly Federated States of Micronesia), as well as Hawaii and Micronesian diaspora communities living in Hawaii.

Beyond this specific sanctuary designation, the federal government should engage with territorial governments to determine the unique needs their citizens have when it comes to ocean conservation: The Biden administration recently announced a federal policy establishing a consultation policy with Native Hawaiians. This should be further extended to all Indigenous peoples in the US Pacific territories, particularly the US territories of Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa. In addition, the federal government uses other models to engage with Native peoples in Alaska and the contiguous United States (i.e. the Northern Bering Sea Climate Resilience Area), and those should be explored to determine the most appropriate way to engage with Indigenous Pacific Islanders.

In addition to Pacific Remote Islands, the Biden administration must advance all of the proposed national marine sanctuaries in various stages of development, which each have varying levels of Indigenous engagement. The ONMS should begin designation of the Alaĝum Kanuux̂ and Mariana Trench national marine sanctuaries. Additionally, NOAA should continue to work alongside the respective Indigenous and local communities as they review comments and prepare draft management plans for the Chumash Heritage, Hudson Canyon, and the Papahānaumokuākea sanctuaries.

Advancing all of the sanctuaries will require NOAA to adequately fund the ONMS. A 2021 Center for American Progress report on sanctuary conditions found that many existing sanctuaries are experiencing worsening conditions, have limited statutory authority to control damaging activities within their borders, and lack sufficient funding. Furthermore, a 2017 study by Gill et al found that staff and budget capacity are critical to achieve conservation impacts. The ONMS today requires more resources to effectively engage Tribes and Indigenous communities as full partners in the design, management, and operation of national marine sanctuaries – particularly those being managed out of the office in Hawaii, which is responsible for four potential designations.

Implementing national marine monuments in the US Pacific territories has proven difficult. Designated in 2009, neither the Mariana Trench nor the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument have final published management plans, and the federal funding that is available mainly goes to offices in Hawaii, not the US Pacific territories. NOAA should consider creating a fund or endowment, similar to the Western Pacific Sustainable Fisheries Fund, to ensure that sanctuary jobs, programs, and funding make their way to front line communities in the US Pacific territories, in line with the Justice40 initiative. A similar fund was created for the designation of Tristan da Cunha in 2021, with seed funding from several philanthropic partners. In addition, 40% of funding available for the proposed sanctuary could go into the fund, and through territorial co-management agreements, local governments could determine how this funding is used to support sanctuary projects.

Sanctuary regulations

Potential socioeconomic, cultural, and biological impacts of sanctuary designation

Prioritize the U.S. Pacific territories with jobs, programs, and funding, and consider headquartering the proposed sanctuary in one of the US Pacific territories, in line with Justice40. The Biden administration’s America the Beautiful initiative should prioritize ocean conservation for these territories, as they are home to the largest, most strongly protected marine areas with the highest levels of biodiversity in the United States. As noted earlier, 99.5 percent of marine reserves in the United States are in the Pacific Islands, but with the exception of Hawaii, the monuments and sanctuaries in the US Pacific territories do not receive federal funding that is proportional to the conservation burden that they carry. In the long run, this lack of funding will harm the United States’ ability to protect ocean resources because capacity and funding are failing to reach front-line ocean conservation communities.

Chamorros, Samoans, and Micronesians want to have input and consultation in the decision-making process and management of the Pacific Remote Islands. Most of the American Pacific territories are unincorporated, meaning that they are owned by, but not part of the United States. American law since the early 1900s considers the people living there, “savage and restless,” “uncivilized,” and unable to understand “Anglo-Saxon principles.” These are Indigenous communities, unrecognized by the federal government and without full constitutional protections or representation in the federal government. NOAA should go beyond their usual level of community engagement to work with these communities, especially considering the directives to better work with Indigenous peoples in America the Beautiful and Justice40.

I have worked with the Center for American Progress, NGOs, and numerous Indigenous partners to put forward recommendations for understanding Indigenous-led conservation, and these lessons can be applied to working with Indigenous communities across Hawaii, American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and the wider Micronesia region. The recommendations are to, (1) Invite Indigenous identity into conservation work, (2) Lift up Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge, (3) Center Indigenous values in conservation, (4) Help Indigenous peoples achieve the responsibilities they carry, and (5) Support Tribal and Indigenous advocacy. There is a tremendous diversity in Indigenous thought in the world today, and these themes may not apply to everywhere and everyone. But across this diversity, there are probably more similarities than differences, just as small-town America shares values and cultures across its geographic diversity.

There remains a great deal of confusion in the US Pacific territories differentiating between the existing Mariana Trench and Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monuments and the proposed Mariana Trench and Pacific Remote Islands National Marine Sanctuaries, especially since the monuments, designated in 2009, as of this writing do not have final management plans and there is only one park ranger working on Saipan. During the scoping process, the government should explain to the communities the difference between sanctuaries and monuments, how they are created, their regulations, their goals, and explain why implementation of the monuments has lagged for more than a decade. Also, there was a public comment period in 2021 for the management plan of the Mariana Trench monument and in 2022 for the five year review of the Mariana Trench sanctuary, and there has been little to no communication with the community on what came of those consultations.

Information regarding historic properties in the entire area under consideration for a sanctuary designation and the potential effects to those historic properties

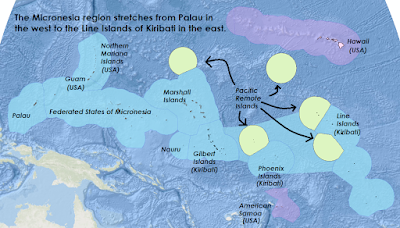

The islands in the Pacific Remote Islands are Micronesian islands. The Micronesia region stretches from Palau in the west to Kiribati in the east. Six of the seven islands abut Micronesian archipelagos, including the Marshall Islands, Phoenix Islands, and Line Islands. The seventh island, Johnston Atoll, is in an area between Micronesia and Hawaii. Voyaging and culture link all of these islands. For example, the shark clan from the Gilbert Islands in Kiribati extends to the Marshall Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia beyond. During the second half of the Twentieth Century, the United States controlled or claimed nearly every Micronesian island between Palau and the Line Islands either as territories, or administered as part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands.

The United States and the Republic of the Marshall Islands both claim Wake Island. In 2016, the Marshalls made their claim formal when they filed maritime coordinates with the United Nations. The ancestors of the people living today in the Marshall Islands named the island Enen-Kio – the island of the orange flower.

The United States gave up claim to several islands which today are part of the Republic of Kiribati with the signing of the Treaty of Tarawa in 1979. While this treaty recognized Kiribati’s sovereignty over 8 Phoenix Islands and 6 Line Islands, the US held on to five nearby islands, Kingman Reef, Palmyra Atoll, Jarvis Island, Howland Island, and Baker Island, so that they could continue to be used for national defense purposes.

Neither the presidential memo directing the secretaries of Interior and Commerce to consider a sanctuary designation, nor the federal register notice of intent to conduct scoping mentions Micronesia. The Pacific Remote Islands initially all became part of the American empire as a result of a mid-nineteenth century law called the Guano Islands Act, and our young nation’s demand for guano fertilizer to feed our growing population and drive our economy. The large areas of ocean surrounding each of these seven islands – what is known as the exclusive economic zone – was claimed in the United States on March 10, 1983 by President Ronald Reagan. With the exception of Johnston Atoll, absent this history of colonization all of the islands within the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument would today be a part of sovereign Micronesian nations. The history, culture, and perspectives of Micronesia and Micronesians needs to be researched and included during scoping, preferably with the inclusion of Micronesian scholars.

For example, the story of the Chamorros who protected Wake Island from invading Japanese soldiers during World War II are absent from the presidential memo and federal register notice. The inclusion of these Chamorro men, along with the story of the Hawaiian Hui Panalā'au – self-identified as a “society of colonizers” – are an opportunity to interpret the shared modern history and culture of Micronesians and Hawaiians and the role this has played and continues to play in the violent colonization of Micronesia. Understanding this shared history provides deeper context, meaning, and understanding to the role American colonization has played in Micronesia and the Pacific, and also reflects on some of the social, economic, and cultural issues that Micronesian immigrants face in Hawaii today. It also brings attention to the role that ongoing colonization and militarization play in the modern conservation movement. The Pacific Remote Islands are best understood through their full historical and cultural context as colonized islands in Micronesia.

Potential boundaries

The spatial extent of the proposed sanctuary, and boundary alternatives NOAA should consider and the location, nature, and value of resources that would be protected by a sanctuary

I do not offer any recommendations on the proposed boundary of the sanctuary, nor on proposed fishing restrictions, other than that they should be agreed upon by all stakeholders and resource owners, particularly those living in the US Pacific territories. This is consistent with my support to the Friends of the Mariana Trench, the leading advocates for the proposed Mariana Trench National Marine Sanctuary. These conversations should be led by the Indigenous Peoples and local communities who live closest to the proposed sanctuary.

In the last decade there has been very limited industrial fishing in the proposed sanctuary area. According to a 2019 report from the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency, from 2013 to 2017, between 0.4% and 3.1% of the US purse seine fleet landings was caught in the US EEZ of American Samoa and the Pacific Remote Islands. This is a de minimus amount, which can easily be replaced by displacing the vessels to the high seas or into the countries where the US fleet has access agreements. In 2015, the last year for which public data is available on the NOAA website, only 0.67% of the Hawaiian longline effort in the Pacific took place in the PRI (effort is measured in terms of hooks set). This is also a de minimus amount, which can easily be replaced by displacing the vessels to the high seas. The proposal to close the region to all fishing, and the process to engage the Indigenous peoples living in the US Pacific territories has created conflict in our communities (see selected list of media at end of this comment). During the sanctuary process, the government should explain to resource owners in the US Pacific territories what biological, cultural, social, and economic costs and benefits will accrue to them, broken down according to the different proposals/options put forward for consideration. The proposal, as written, would put all of the burden on the territories, with most of the benefits accruing to people outside of the US Pacific territories.

The government should use the vocabulary in the MPA Guide to communicate levels of protection and stage of establishment of any proposed protected areas within the proposed sanctuary. The MPA Guide can help government decision makers and community members better understand the biological and social outcomes of different proposed types of marine protected areas, from fully/highly protected to lightly/minimally protected. The MPA Guide also helps government decision makers understand when and under what socio-economic cultural conditions biological benefits accrue.

Media From the US Pacific Territories:

Effort to Expand Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument Gets Pushback, Hawaii News Now, September 23, 2022

Amata Welcomes Biden Administration Response That Marine National Monument Will Not Be Expanded, Press Release, October 6, 2022. Republished in Marianas Variety.

Biden to Expand Pacific Remote Islands Marine Monument, Pacific Times, March 22, 2023.

Amata Raises Concerns About Massive New 777,000 Square Miles of NMS Around the Pacific Remote Islands, Press Release, March 23, 2023. Republished in Samoa News, Marianas Variety.

President Biden Goes Back On Word Regarding PRIMNM, Talanei, March 23, 2023.

American Samoa Delegate Nixes Expansion Plan for Pacific Remote Islands Sanctuary, Pacific Island Times, March 25, 2023

Congresswoman Amata opposes Pacific Remote Islands expansion plan, Island Business, March 27, 2023.

Concern raised over Biden’s marine sanctuary initiative, Hawaii Public Radio, March 27, 2023

Protests Mount Over Biden’s Expansion Plan for Pacific Remote Island Monument, March 28, 2023

American Samoa Official Slams Biden’s Pacific Monument Expansion Proposal, Undercurrent News, March 28, 2023.

CNMI Governor Palacios Urges President Biden to Respect Pacific Island Communities, Press Release, March 29, 2023. Republished in Saipan Tribune.

Community Members Oppose Expansion of Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, Marianas Variety, March 29, 2023.

Issues of Fairness, Equity, and Respect Dominate Fishery Management Council, Press Release, April 4, 2023. Reprinted in Samoa News.

NOAA Begins Process for Biden’s Proposed Marine Sanctuary, Seafood Source, April 20, 2023.

Governor Tells President Biden to Reconsider Sanctuary Plan, Talanei, April 26, 2023

American Samoa Criticizes US Plan to Expand Size of Pacific Marine Sanctuary, Radio Free Asia, April 27, 2023. Reprinted by Pacific Islands News Association, Marianas Variety, Island Times.

Marine Sanctuary Expansion Alarms Pacific Governors, Marianas Variety, May 1, 2023. Reposted in Guam Daily Post.

The Burden of Territorial Status, Pacific Island Times, May 2, 2023

US Pacific Territory Governors Seek White House Meeting to Oppose Marine Sanctuary Expansion, Undercurrent News, May 3, 2023

Marine Sanctuary Expansion Alarms Pacific Governors, Islands Business, May 4, 2023. Republished in Pasifika Environews.

Congresswoman Supports Governor’s Request for Meeting with Biden, Talanei, May 4, 2023

Hawaii Weighs in on Proposed Marine Sanctuary for Remote Pacific Islands, Civil Beat, May 11, 2023

Guam Residents Can Provide Input on Proposed Marine Sanctuary, The Guam Daily Post, May 15, 2023

A Marine Sanctuary Proposal Raises Concerns From Residents, The Guam Daily Post, May 18, 2023

“Lively Discussion” Expected at Marine Sanctuary Public Meetings, Marianas Variety, May 18, 2023

CNMI Resident Oppose National Marine Sanctuary, KUAM, May 19, 2023

Locals Testify Against Expanding Marine Monument, Marianas Variety, May 22, 2023

Pacific Voices Being Disrespected; Process is not Pacific Way, Saipan Tribune, May 22, 2023

Guam Fishermen Jeer NOAA Monument Expansion at Meeting, Undercurrent News, May 23, 2023

Study: Pacific Tuna Fleets Rarely Fish in Waters Proposed for New Sanctuary, Civil Beat, May 23, 2023

Comments

Post a Comment