There is a renaissance in Indigenous culture and identity stretching across the Pacific today, and it will only achieve its full potential with an equal renaissance in ocean conservation. We need more places in the ocean where Nature exists as the Creator intended, a place where fish, birds, and other animals and their connections to Pacific people can thrive free from the damaging effects of modern development and extraction. It was in a world such as this that the first humans to cross the Pacific became Native Pacific Islanders, and it was in this world that the Disney film 'Moana' takes place.

'Moana' tells the story about the daughter of the village chief, who is chosen by the ocean herself to cross the sea in search of the demi-god Maui to force him to help her save her village by returning the stolen heart of the goddess Te Fiti. If that's confusing, just think of it as Lord of the Rings (shoeless young person returns stolen jewelry) meets Call it Courage (island kid goes on an adventure and comes home awesome) with songs.

Early in the film, Moana learns that her people are descended from voyagers -- something that everyone in the village had collectively forgotten. Then she goes off on her adventure, learns how to wayfind and sail from the demi-god Maui, defeats a giant coconut crab and a lava monster, and saves the world!

While she uses the stars, the winds, and the clouds, to sail her canoe, it is her education that she uses to navigate her epic adventure. It is this knowledge that Moana uses to save the world, and unfortunately for her, in the beginning of the film she doesn't know very much. She wrecks her first canoe on the reef. Then she's not a particularly good sailor once she gets the second canoe from the hidden cave. Then she gets captured by the giant singing coconut crab. And it's her fault that Maui's giant magic hook almost gets destroyed in the first battle with the lava monster (this all makes so much more sense if you've seen the movie).

Repeatedly Moana comes up with a plan based on her best available evidence, then tests it, fails, and realizes it was a really bad plan. So she refines the plan, tests it again, and succeeds -- most of the time. That's not just good story telling, that's the scientific method!

Moana is not a Disney princess. She's a Polynesian scientist! And she's helping me make arguments for why we need large scale marine protected areas in the ocean. Let me explain:

The scientific method is also how traditional wayfinding, so central to the story of Moana, developed in the real world. Traditional wayfinding, voyaging across the ocean without the use of modern navigation tools, as it is practiced today, developed over time using observations of the natural environment such as the sun, moon, stars, cloud movements, wind, ocean swells, and birds and fish to sail across the sea. This knowledge was obtained over centuries and was passed down from teacher to student using chants in the oral tradition.

The fact that Moana's people had forgotten they were voyagers mirrors real life. By the middle of the 20th Century, voyaging had completely disappeared from Polynesia and most western experts questioned whether humans could have purposely crossed the Pacific without the use of modern navigation tools. The last vestiges of traditional wayfinding were only found on a few small atolls in Micronesia, known by a dwindling number of master navigators.

That all changed in 1976 when Mau Pialug, a 44 year old navigator from the island of Satawal in the Federated States of Micronesia, shared his knowledge of wayfinding with the Polynesian Voyaging Society and successfully guided a canoe from Hawaii to Tahiti (paralleling the story of Moana). That first in centuries feat led to a renaissance of traditional voyaging and culture in Hawaii and across the entire Pacific. Today there are navigators in many countries, including Hawaii, New Zealand, and Tahiti.

Early in the film, Moana learns that her people are descended from voyagers -- something that everyone in the village had collectively forgotten. Then she goes off on her adventure, learns how to wayfind and sail from the demi-god Maui, defeats a giant coconut crab and a lava monster, and saves the world!

"I am everything I've learned and more."

--Moana

While she uses the stars, the winds, and the clouds, to sail her canoe, it is her education that she uses to navigate her epic adventure. It is this knowledge that Moana uses to save the world, and unfortunately for her, in the beginning of the film she doesn't know very much. She wrecks her first canoe on the reef. Then she's not a particularly good sailor once she gets the second canoe from the hidden cave. Then she gets captured by the giant singing coconut crab. And it's her fault that Maui's giant magic hook almost gets destroyed in the first battle with the lava monster (this all makes so much more sense if you've seen the movie).

Repeatedly Moana comes up with a plan based on her best available evidence, then tests it, fails, and realizes it was a really bad plan. So she refines the plan, tests it again, and succeeds -- most of the time. That's not just good story telling, that's the scientific method!

Moana is not a Disney princess. She's a Polynesian scientist! And she's helping me make arguments for why we need large scale marine protected areas in the ocean. Let me explain:

The scientific method is also how traditional wayfinding, so central to the story of Moana, developed in the real world. Traditional wayfinding, voyaging across the ocean without the use of modern navigation tools, as it is practiced today, developed over time using observations of the natural environment such as the sun, moon, stars, cloud movements, wind, ocean swells, and birds and fish to sail across the sea. This knowledge was obtained over centuries and was passed down from teacher to student using chants in the oral tradition.

"We are explorers reading every sign."

--Moana's wayfinding ancestor

The fact that Moana's people had forgotten they were voyagers mirrors real life. By the middle of the 20th Century, voyaging had completely disappeared from Polynesia and most western experts questioned whether humans could have purposely crossed the Pacific without the use of modern navigation tools. The last vestiges of traditional wayfinding were only found on a few small atolls in Micronesia, known by a dwindling number of master navigators.

That all changed in 1976 when Mau Pialug, a 44 year old navigator from the island of Satawal in the Federated States of Micronesia, shared his knowledge of wayfinding with the Polynesian Voyaging Society and successfully guided a canoe from Hawaii to Tahiti (paralleling the story of Moana). That first in centuries feat led to a renaissance of traditional voyaging and culture in Hawaii and across the entire Pacific. Today there are navigators in many countries, including Hawaii, New Zealand, and Tahiti.

There are numerous ways traditional knowledge, modern Western science, and the need for conservation can be tied together. For example, one tool that navigators use to find their target islands are birds. Depending on the species, the direction it is flying, and the time of day, wayfinders can use birds to help them expand the target area of the islands they are trying to find. This is because certain birds are spotted at predictable distances from islands. This knowledge has been known to wayfinders for centuries.

This phenomena is captured in the song 'We Know the Way' from the film. In the clip, Moana realizes that she's descended from voyagers, and as she does she receives a vision from her ancestors. The navigators ply the open seas day and night, in the rain and sun, and then just as the song is ending, a bird flying overhead guides the navigator and the canoes to their target island.

This phenomena is captured in the song 'We Know the Way' from the film. In the clip, Moana realizes that she's descended from voyagers, and as she does she receives a vision from her ancestors. The navigators ply the open seas day and night, in the rain and sun, and then just as the song is ending, a bird flying overhead guides the navigator and the canoes to their target island.

|

| The bird guides the voyagers to the island. |

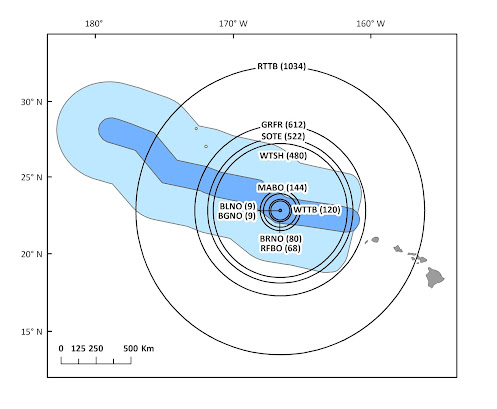

Modern science has 'discovered' this phenomena, too. Studies have found that different species of seabirds can be found at predicatable distances from their nesting islands, which is likely due to interspecies competition for feeding on small fish. Some species, like the black noddy (Anous minutus) and the blue grey noddy (Procelsterna cerulean) stay relatively close to shore, looking for food in a radius around their home islands not much greater than 9 kilometers. Red tailed tropic birds (Phaethon rubricauda), on the other hand, venture as far as 1034 kilometers from their nests in search for food. Other species where these distances are known include boobies, shearwaters, and frigate birds.

|

| Concentric circles show range of different foraging bird species while nesting. Graphic from Maxwell & Morgan 2013 |

The reason the birds fly out over the ocean is to search for small forage fish that school in tight groups after being forced close to the surface by larger predators such as sharks and tuna. As the sharks and tuna attack the forage fish from below, seabirds hone in from above. Smallboat fishermen around the world know about this phenomena and search out flocks of birds in search of fish.

|

| Ocean predators facilitate seabird foraging by forcing small fish to the surface. Graphic from Maxwell & Morgan, 2013. |

While the voyagers depend on the birds to find their target islands, the birds depend on the big predators to find the forage fish; the forage fish would not school at the surface if not for the predators. It stands to reason that if there are no predators, or reduced numbers of predators, the schools of small fish will not be forced to the surface, and as a result the birds are going to end up in the wrong place, which in turn has the chance to lead voyagers astray.

This is a real worry. The numbers of ocean predators have declined precipitously in the last 100 years. Pacific Bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis) and bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus) are now assessed as threatened with extinction by the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species. As for sharks, more than 100 million are killed each year in fisheries. As a result, the populations of more than half of all shark species assessed by the IUCN Red List are threatened or near threatened with extinction. Some populations, like oceanic whitetip sharks (Carcharhinus longimanus) in the Gulf of Mexico, have declined by as much as 99%.

But all is not lost. There are still places in our ocean that are healthy, and places where it can return to its prior abundance. For example, the Northwest Hawaiian Islands, now the highly protected Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument, stretch across more than one and a half million square kilometers in the central Pacific ocean. These waters are sanctuary for sharks, whales, fish, turtles, and birds, but are also a sanctuary for Hawaiian culture to grow and flourish. In these protected waters, Native Hawaiians aboard traditional vessels can reconnect with their identify and learn about who they are and where they are going as a people.

This is a real worry. The numbers of ocean predators have declined precipitously in the last 100 years. Pacific Bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis) and bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus) are now assessed as threatened with extinction by the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species. As for sharks, more than 100 million are killed each year in fisheries. As a result, the populations of more than half of all shark species assessed by the IUCN Red List are threatened or near threatened with extinction. Some populations, like oceanic whitetip sharks (Carcharhinus longimanus) in the Gulf of Mexico, have declined by as much as 99%.

But all is not lost. There are still places in our ocean that are healthy, and places where it can return to its prior abundance. For example, the Northwest Hawaiian Islands, now the highly protected Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument, stretch across more than one and a half million square kilometers in the central Pacific ocean. These waters are sanctuary for sharks, whales, fish, turtles, and birds, but are also a sanctuary for Hawaiian culture to grow and flourish. In these protected waters, Native Hawaiians aboard traditional vessels can reconnect with their identify and learn about who they are and where they are going as a people.

This renaissance in culture and Pacific identify has grown in parallel with the modern environmental movement, particularly the growth of large scale marine protected areas around the world. The need to protect large swaths of ocean should be obvious to anyone who has ever visited the national parks in the United States. Yellowstone National Park is the greatest example of America's natural heritage, and if it had not been protected in 1872, the trees would have been cut down long ago to make way for highways and cities.

Similarly, the only way our grandchildren will have areas of the ocean that are left as the Creator made them is if we identify and protect them today. And while it's important to have areas that are close to shore for all the reasons that marine protected areas are created, it also makes sense to protect huge swaths of ocean just like we've been protecting huge swaths of land for nearly 150 years.

Protecting ocean ecosystems is going to have to be a priority if the renaissance in Pacific culture is going to continue. As Jane Lubchenco and Kirsten Grorud Colvert pointed out in an article in Smithsonian Magazine, for most of history, the ocean was a de facto fully protected area, simply because humans could not access it. In order for wayfinders to have the full suite of navigational tools available to them, they will require healthy, intact ocean ecosystems, particular those provided by large scale marine protected areas.

Similarly, the only way our grandchildren will have areas of the ocean that are left as the Creator made them is if we identify and protect them today. And while it's important to have areas that are close to shore for all the reasons that marine protected areas are created, it also makes sense to protect huge swaths of ocean just like we've been protecting huge swaths of land for nearly 150 years.

Protecting ocean ecosystems is going to have to be a priority if the renaissance in Pacific culture is going to continue. As Jane Lubchenco and Kirsten Grorud Colvert pointed out in an article in Smithsonian Magazine, for most of history, the ocean was a de facto fully protected area, simply because humans could not access it. In order for wayfinders to have the full suite of navigational tools available to them, they will require healthy, intact ocean ecosystems, particular those provided by large scale marine protected areas.

"For most of its history, the ocean was a de facto fully protected area, simply because humans could not access it. It is only in the last half-century that most of the ocean has become accessible to extractive activities."

-- Jane Lubcheno & Kirsten Grorud-Colvert

I published a version of this on The Saipan Blog in 2017

Comments

Post a Comment